Why Screen Readers Are Imperative in Accessibility Testing

When we talk about accessibility testing, it is generally believed that manual testing is more handy than automated techniques. While this may largely be true, assistive tools are imperative in aiding the manual test effort, especially when testing accessibility for those with low, limited, or no vision.

Say, for instance, a web page is being tested for accessibility by a person who is hearing-impaired. The main check is to ensure that there are captions for videos and transcripts for audio—assistive tools are not critical here. Similarly, for locomotor users, the prime check involves ensuring all page elements are accessible via the keyboard—a standard piece of office equipment. Unlike these disabilities, for the visually impaired, the use of screen readers is almost mandatory to ensure an application is fully accessible.

Screen readers have existed for a long time and have evolved with the changes in the technology world. There are different kinds of screen readers for every platform. For Windows, we have JAWS and NVDA; for Mac, we have VoiceOver, which comes built in; and for Linux, we have 70 to 75 percent of accessibility test coverage, especially for Section 508 and WCAG compliance. While we understand the value of screen readers, can accessibility testing for the visually challenged be done without them? The answer is yes—well, at least to some extent. There are several automation tools, such as the Web Accessibility Toolbar from Vision Australia and WAVE from WebAIM, that help validate a page per accessibility guidelines.

While automation tools bring in test repeatability and support the manual effort, they have some stark gaps. For example, an automation tool can identify the availability of alt tags for images on a page, but it cannot confirm the tags are correct or appropriate.

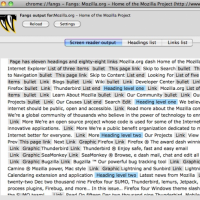

A screen reader lets a tester experience the real-time challenges faced by a user who is visually challenged. The screen reader is able to navigate through important elements such as headings, which give the right structure for the web page; correct labeling for form fields; an appropriate title and summary; and logical and correct association for tables, all of which together enable the required levels of accessibility. Even simple errors such as typos on a page or lack of resolution in an image are better caught with a screen reader.

Visual impairment being one of the significant categories under the disability umbrella, a screen reader is a must-have tool in an accessibility tester’s toolkit. It has minimal key combinations and syntax that the user has to learn to be able to use the tool fully. While any tester can learn to use a screen reader in a few days, the true value is reaped when a real visually impaired user uses a screen reader to test an application.